Designing A Circuit Breaker For Disabling Webhook Endpoints

This post was originally posted on Convoy’s blog.

One of the major problems that arose when designing Convoy, a webhook delivery system is figuring out what to do when you have bad/zombie endpoints. Zombie endpoints are endpoints that fail continuously and, over time, clog up your queues, create back pressure, and delay webhook delivery to functioning endpoints. Circuit breakers are the best-known mechanism for dealing with unreliable HTTP API endpoints, preventing failures from upstream services from cascading into our system.

In this article, we describe the design of a stateful distributed circuit breaker used to handle zombie endpoints in Convoy. But before we dive into its design, let’s look at a quick refresher on the circuit breaker API and how it works. Let’s consider a circuit breaker used when calling Stripe’s APIs.

circuit := manager.GetCircuit("stripe")

err := circuit.Run(ctx, func(ctx context.Context) error {

// ...

// charge card or any other Stripe action.

// ...

return err

}

In the above, we retrieve the circuit used to manage calls to the Stripe API and wrap the current call to the API with the circuit.Run() method. The circuit breaker does two things:

- It tracks the success/failure of past calls

- It decides whether the current call should go through.

The state of the circuit breaker is local to each process, so if you have ten processes, each must come to this realization independently (this is by design). The libraries below evaluate and manage circuit breakers this way:

You can read more about circuit breakers here and here.

Synchronous vs. Asynchronous circuit breakers

Synchronous Circuit Breakers

Synchronous circuit breakers operate in a blocking manner when performing health checks. When evaluating the next state for a circuit breaker, all subsequent calls for the circuit breaker will be blocked until it is complete. This is a straightforward approach, but it can lead to performance issues, as the calling services are forced to wait for the operation to complete before proceeding. This blocking behavior is commonly implemented with a mutex or a semaphore. The libraries mentioned above are examples of Synchronous circuit breakers.

The main advantages of synchronous circuit breakers are:

- Simplicity: Synchronous circuit breakers are relatively easy to implement and understand.

- Visibility: The state of the circuit breaker is clearly visible, making it easier to monitor and troubleshoot.

The disadvantages of synchronous circuit breakers include:

- No Synchronization Across Replicas: Since each server runs its version of the circuit breaker, each server realizes the state of the third-party service or an upstream endpoint on its own without a means to let the other servers know about its findings. If a decision needs to be made to switch to a fallback provider or disable an endpoint, a new replica that is spun up will still attempt to send requests to that failing third-party service.

- Reduced Concurrency: Synchronous circuit breakers limit the system’s concurrency, as each request must wait for the circuit breaker state evaluation to complete before it can proceed.

Asynchronous Circuit Breakers

Asynchronous circuit breakers, on the other hand, operate in a non-blocking manner. That is, state evaluation is decoupled from usage. This allows the system to maintain higher availability and concurrency, as calling services can process requests while the new state is being evaluated.

The main advantages of asynchronous circuit breakers are:

- Improved Availability: Asynchronous circuit breakers do not block the calling service, allowing the system to maintain a higher level of availability.

- Increased Concurrency: Asynchronous circuit breakers can handle more concurrent requests, as the calling service is not blocked while the circuit breaker is tripped.

- Synchronization Across Replicas: Each server replica is aware of the new state of the circuit breaker and uses that when making decisions. When decisions are made, all replicas receive the update. Also, while they don’t all get the update on time, the time lag isn’t as drawn out as it would be if it had to come to the same conclusion.

The disadvantages of asynchronous circuit breakers include:

- Increased Complexity: Asynchronous circuit breakers are generally more complex to implement and understand, requiring additional logic to handle the non-blocking behavior.

- Reduced Visibility: The state of the circuit breaker may not be as easily visible as in the synchronous case, making it more challenging to monitor and troubleshoot.

Our Circuit Breaker Requirements

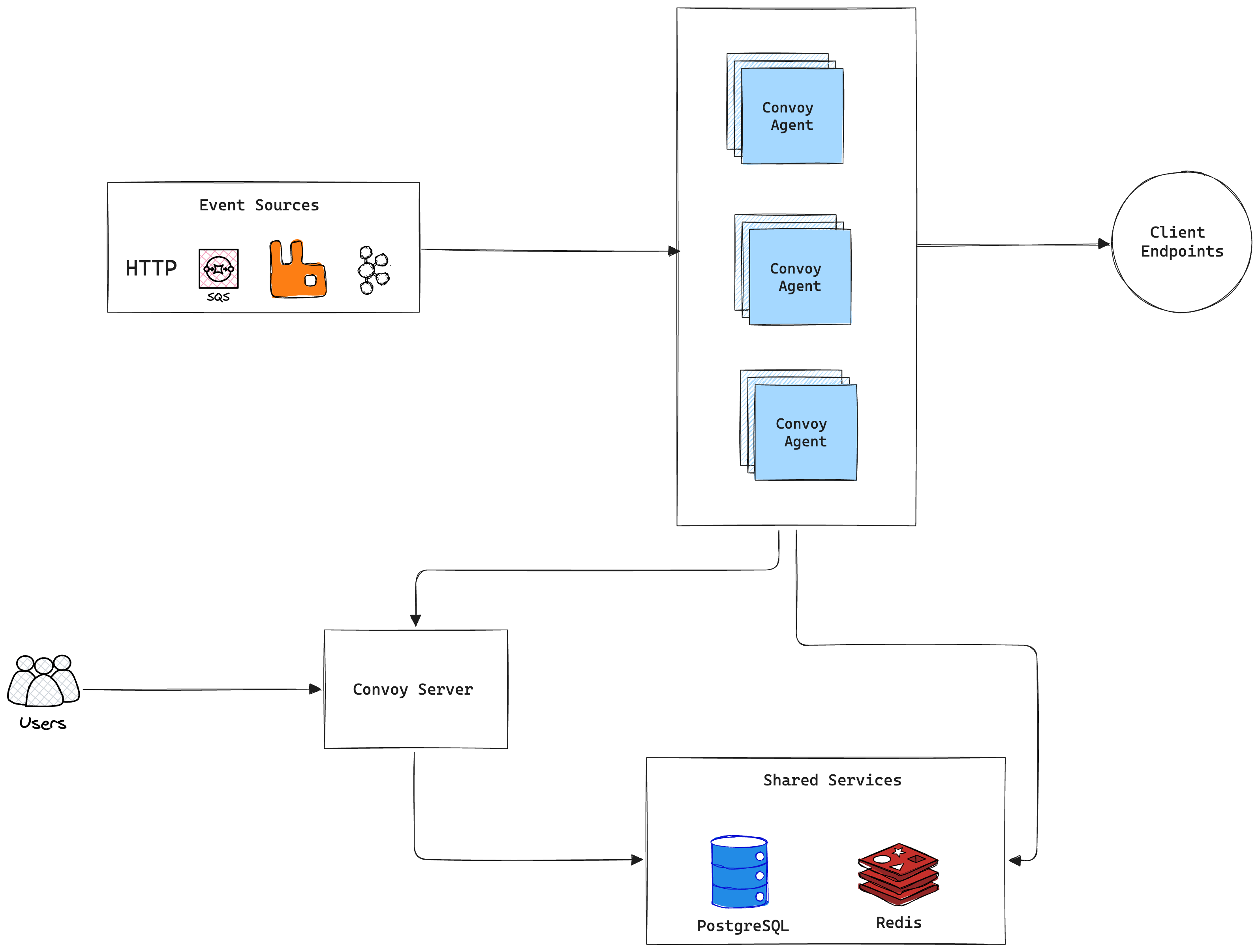

Before we go into the details of a distributed circuit breaker, let’s refresh our knowledge of Convoy’s architecture. Convoy's architecture

Convoy's architecture

Convoy’s agent is responsible for ingesting, queueing, and dispatching webhook events; essentially, it is the hot path on which we must apply our circuit breakers. Now, we have sufficient background to dive into the details of the distributed breaker and how it differs from traditional circuit breakers.

Core Requirements

- Design a circuit breaker that can disable webhook delivery to an endpoint across all agents.

- Design the system without introducing another dependency for leader election.

The first requirement is the most important requirement to the design of an asynchronous circuit breaker. We need a mechanism to enable the system to conclude that the webhook endpoint has failed and should be disabled so that any agent attempting to send a webhook to that endpoint doesn’t. The second requirement is a self-imposed limitation [1] that forced us to not over-engineer the chosen solution.

An important distinction between a synchronous and asynchronous circuit breaker is that the former is used to manage only a handful of endpoints; when the a circuit trips excessively, on-call engineers are paged to fix the issue, while the latter is used to manage more than a handful — in our scenario, webhook endpoints that can grow to thousands. Paging on-call engineers for each failure isn’t a feasible solution; the system needs to come to the conclusion by itself and notify the customer.

Before I get into our solution, let’s explore some alternatives evaluated:

Solution #1: Using Redis and Etcd

Shared Metrics in Redis

- All agents increment the number of requests and failures in Redis using atomic operations.

State Management in Etcd

- Use

etcdto store the circuit breaker state. - Implement leader election using

etcd. - Only the leader can update the circuit breaker state using the metrics from Redis, and the other agents (followers) can only read it.

Workflow:

- When writing;

- Agents send webook requests and update Redis with the result (success/failure).

- The leader agent periodically checks the metrics from Redis and determines if the circuit breaker should change state.

- If the state needs to change, the leader updates the state in

etcd.

- When reading;

- Each agent reads the state from

etcdbefore sending an event.

- Each agent reads the state from

Pros

- Metrics collection is decoupled from the decision-making process.

- We get industry-standard leader-election baked into the system automatically.

Cons

- This would require us to add a new dependency, which would be a deal breaker as running in our cloud environment would cost more per customer, and our community members would have to learn how to host and run an

etcdcluster.

Solution #2: Using Redis and PostgreSQL: LISTEN/NOTIFY + leader election using RedLock

PostgreSQL triggers the event

- Whenever the status of an event delivery changes, an ON-UPDATE SQL event is triggered from the event deliveries table. The trigger runs a function that sends a notification message from Postgres to the app using

NOTIFY.

State management in Redis

- The leader agent

LISTEN(s) to the channel; when it receives a message, it updates the circuit breaker’s state based on the failure rate and stores the new state in Redis. - A background job is run on the leader periodically to transition each breaker’s state from

opentohalf-openwhen the timeout has elapsed.

Workflow

- When writing;

- Each agent tries to acquire a distributed lock using Redlock; only one succeeds and holds it until it is done, while the other agents’ lock requests expire.

- Write the updated circuit breaker state to redis

- Release the distributed lock

- When reading;

- Each agent fetches the circuit breaker state from Redis before sending an event.

Pros

- Row-level database triggers are thread-safe since each trigger is executed in the same transaction context, and Go’s mutex locks will serialize the concurrent operation [3]

Cons

- For every event delivery sent, the database trigger runs and generates a notification, which could lead to the listener doing a disproportionate amount of work when many events are sent in a short period.

- Metrics collection information can be lost if an error occurs in the listener’s handler or when the leader election event is happening since there is no leader at that point.

- Row-level database triggers significantly affect query performance by about 3x. [4]

Our Solution: Use Redis and Postgres Database Polling + leader election using RedLock

This was inspired by AWS’s Do Constant Work [6] philosophy. We chose this approach because it is deterministic and easy to grok. Polling will take a toll on the db for sure, but with relatively good indexes and a reasonable poll interval the db hit won’t be noticeable.

PostgreSQL

- Samples a set of rows based on an observability window from an SQL table to calculate success and failure rates.

Redis

- We use a distributed lock on Redis to select the leader node [1].

- The leader loads the circuit breaker state; if it exists it will update it based on the success and failure rates from the db poll result, if not it will create a new one, and then it will store the new states in Redis.

- All agents load the circuit breaker state from Redis into memory when making decisions.

Workflow

- When writing;

- Each agent tries to acquire a distributed lock using Redlock; only one succeeds and holds it until it is done, while the other agents’ lock requests expire.

- Samples a set of rows based on an observability window from an SQL table to calculate success and failure rates.

- Load the circuit breaker state and update it based on the success and failure rates or the timeout expired (for

opencircuit breakers). - Store the new state in Redis.

- Release the lock.

- The whole process is run periodically based on a sample rate.

- When reading;

- Each agent fetches the circuit breaker state from Redis before sending an event.

Implementation

The code for the package is here if you want to browse the whole thing. Now we can go into details about the part of the package.

Circuit Breaker

A circuit breaker represents an upstream endpoint or a 3rd party service.

// State represents a state of a CircuitBreaker.

type State int

// These are the states of a CircuitBreaker.

const (

StateClosed State = iota

StateHalfOpen

StateOpen

)

// CircuitBreaker represents a circuit breaker

type CircuitBreaker struct {

// Circuit breaker key

Key string `json:"key"`

// Circuit breaker tenant id

TenantId string `json:"tenant_id"`

// Circuit breaker state

State State `json:"state"`

// Number of requests in the observability window

Requests uint64 `json:"requests"`

// Percentage of failures in the observability window

FailureRate float64 `json:"failure_rate"`

// Percentage of failures in the observability window

SuccessRate float64 `json:"success_rate"`

// Time after which the circuit breaker will reset when in half-open state

WillResetAt time.Time `json:"will_reset_at"`

// Number of failed requests in the observability window

TotalFailures uint64 `json:"total_failures"`

// Number of successful requests in the observability window

TotalSuccesses uint64 `json:"total_successes"`

// Number of consecutive circuit breaker trips

ConsecutiveFailures uint64 `json:"consecutive_failures"`

logger *log.Logger

}

Circuit Breaker Manager

We use a CircuitBreakerManager to manage all the circuit breakers. It comes bundled with a Store, Configuration, and Clock.

type CircuitBreakerManager struct {

config *CircuitBreakerConfig

logger *log.Logger

clock clock.Clock

store CircuitBreakerStore

}

Configuring the CircuitBreakerManager

We expose Configuration options that allow us to tune the sample rate, timeout duration, etc.

// CircuitBreakerConfig is the configuration that all the circuit breakers will use

type CircuitBreakerConfig struct {

// SampleRate is the time interval (in seconds) at which the data source

// is polled to determine the number successful and failed requests

SampleRate uint64 `json:"sample_rate"`

// BreakerTimeout is the time (in seconds) after which a circuit breaker goes

// into the half-open state from the open state

BreakerTimeout uint64 `json:"breaker_timeout"`

// FailureThreshold is the % of failed requests in the observability window

// after which a circuit breaker will go into the open state

FailureThreshold uint64 `json:"failure_threshold"`

// MinimumRequestCount minimum number of requests in the observability window

// that will trip a circuit breaker

MinimumRequestCount uint64 `json:"request_count"`

// SuccessThreshold is the % of successful requests in the observability window

// after which a circuit breaker in the half-open state will go into the closed state

SuccessThreshold uint64 `json:"success_threshold"`

// ObservabilityWindow is how far back in time (in minutes) the data source is

// polled when determining the number successful and failed requests

ObservabilityWindow uint64 `json:"observability_window"`

// ConsecutiveFailureThreshold determines when we ultimately disable the endpoint.

// E.g., after 10 consecutive transitions from half-open → open we should disable it.

ConsecutiveFailureThreshold uint64 `json:"consecutive_failure_threshold"`

}

Store

We define a Store interface that describes access methods for circuit breaker state storage and distributed lock management.

type CircuitBreakerStore interface {

// Lock used to acquire a distributed lock

Lock(ctx context.Context, lockKey string, expiry uint64) (*redsync.Mutex, error)

// Unlock is used to release a distributed lock

Unlock(ctx context.Context, mutex *redsync.Mutex) error

// Keys returns all the keys which match the given pattern

Keys(context.Context, string) ([]string, error)

// GetOne returns the value given a key

GetOne(context.Context, string) (string, error)

// GetMany returns all the values given many keys

GetMany(context.Context, ...string) ([]interface{}, error)

// SetOne sets a key-value in the store

SetOne(context.Context, string, interface{}, time.Duration) error

// SetMany set the value of many keys

SetMany(context.Context, map[string]CircuitBreaker, time.Duration) error

}

Clock

Finally, we define a Clock interface, which we can mock when running tests.

// A Clock is an object that can tell you the current time.

//

// This interface allows decoupling code that uses time from the code that creates

// a point in time. You can use this to your advantage by injecting Clocks into interfaces

// rather than having implementations call time.Now() directly.

//

// Use RealClock() in production.

// Use SimulatedClock() in test.

type Clock interface {

Now() time.Time

}

Initializing the CircuitBreakerManager

Next, we provide a constructor function to initialize the CircuitBreakerManager instance.

func NewCircuitBreakerManager(options ...CircuitBreakerOption) (*CircuitBreakerManager, error) {

r := &CircuitBreakerManager{}

for _, opt := range options {

err := opt(r)

if err != nil {

return r, err

}

}

if r.store == nil {

return nil, ErrStoreMustNotBeNil

}

if r.clock == nil {

return nil, ErrClockMustNotBeNil

}

if r.config == nil {

return nil, ErrConfigMustNotBeNil

}

if r.logger == nil {

return nil, ErrLoggerMustNotBeNil

}

return r, nil

}

// use it like this

manager, err := NewCircuitBreakerManager(

StoreOption(store),

ClockOption(clock),

ConfigOption(config),

LoggerOption(log.NewLogger(os.Stdout)),

)

The CircuitBreakerManager exposes methods to

Check if an operation should be allowed

// CanExecute checks if the circuit breaker for a key will return an error for the current state.

// It will not return an error if it is in the closed state or half-open state when the failure

// threshold has not been reached, it will also fail-open if the circuit breaker is not found.

func (cb *CircuitBreakerManager) CanExecute(ctx context.Context, key string) error {

b, err := cb.GetCircuitBreaker(ctx, key)

if err != nil {

return err

}

if b != nil {

return cb.getCircuitBreakerError(b)

}

return nil

}

func (cb *CircuitBreakerManager) getCircuitBreakerError(b *CircuitBreaker) error {

switch b.State {

case StateOpen:

return ErrOpenState

case StateHalfOpen:

if b.FailureRate > float64(cb.config.FailureThreshold) && b.WillResetAt.After(cb.clock.Now()) {

return ErrTooManyRequests

}

return nil

default:

return nil

}

}

Acquire and release the distributed lock.

func (cb *CircuitBreakerManager) sampleAndUpdate(ctx context.Context, pollFunc PollFunc) error {

...

mu, err := cb.store.Lock(ctx, mutexKey, cb.config.SampleRate)

if err != nil {

isLeader = false

cb.logger.WithError(err).Debugf("[circuit breaker] failed to acquire lock")

return err

}

defer func() {

...

innerErr := cb.store.Unlock(ctx, mu)

if innerErr != nil {

cb.logger.WithError(innerErr).Debugf("[circuit breaker] failed to unlock mutex")

}

...

}()

...

// Get the failure and success counts from the last X minutes

pollResults, err := pollFunc(ctx, cb.config.ObservabilityWindow, resetMap)

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("poll function failed: %w", err)

}

if len(pollResults) == 0 {

return nil // Nothing to update

}

if err = cb.sampleStore(ctx, pollResults); err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("[circuit breaker] failed to sample events and update state: %w", err)

}

return nil

}

Sample the database, update the circuit breaker state, and write back to Redis.

func (cb *CircuitBreakerManager) sampleStore(ctx context.Context, pollResults map[string]PollResult) error {

redisCtx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(ctx, 5*time.Second)

defer cancel()

circuitBreakers := make(map[string]CircuitBreaker, len(pollResults))

keys, tenants, j := make([]string, len(pollResults)), make([]string, len(pollResults)), 0

for k := range pollResults {

tenants[j] = pollResults[k].TenantId

key := fmt.Sprintf("%s%s", prefix, k)

keys[j] = key

j++

}

res, err := cb.store.GetMany(redisCtx, keys...)

if err != nil {

return err

}

// marshall res values into circuitBreaker map

...

// calculate the new state for each circuit breaker

for key, breaker := range circuitBreakers {

k := strings.Split(key, ":")

result := pollResults[k[1]]

breaker.TotalFailures = result.Failures

breaker.TotalSuccesses = result.Successes

breaker.Requests = breaker.TotalSuccesses + breaker.TotalFailures

if breaker.Requests == 0 {

breaker.FailureRate = 0

breaker.SuccessRate = 0

} else {

breaker.FailureRate = float64(breaker.TotalFailures) / float64(breaker.Requests) * 100

breaker.SuccessRate = float64(breaker.TotalSuccesses) / float64(breaker.Requests) * 100

}

if breaker.State == StateHalfOpen && breaker.SuccessRate >= float64(cb.config.SuccessThreshold) {

breaker.Reset(cb.clock.Now().Add(time.Duration(cb.config.BreakerTimeout) * time.Second))

} else if breaker.State != StateOpen && breaker.Requests >= cb.config.MinimumRequestCount {

if breaker.FailureRate >= float64(cb.config.FailureThreshold) {

breaker.trip(cb.clock.Now().Add(time.Duration(cb.config.BreakerTimeout) * time.Second))

}

}

if breaker.State == StateOpen && cb.clock.Now().After(breaker.WillResetAt) {

breaker.toHalfOpen()

}

circuitBreakers[key] = breaker

}

// write the updated state back to the store

if err = cb.updateCircuitBreakers(ctx, circuitBreakers); err != nil {

cb.logger.WithError(err).Error("[circuit breaker] failed to update state")

return err

}

return nil

}

Benefits in production?

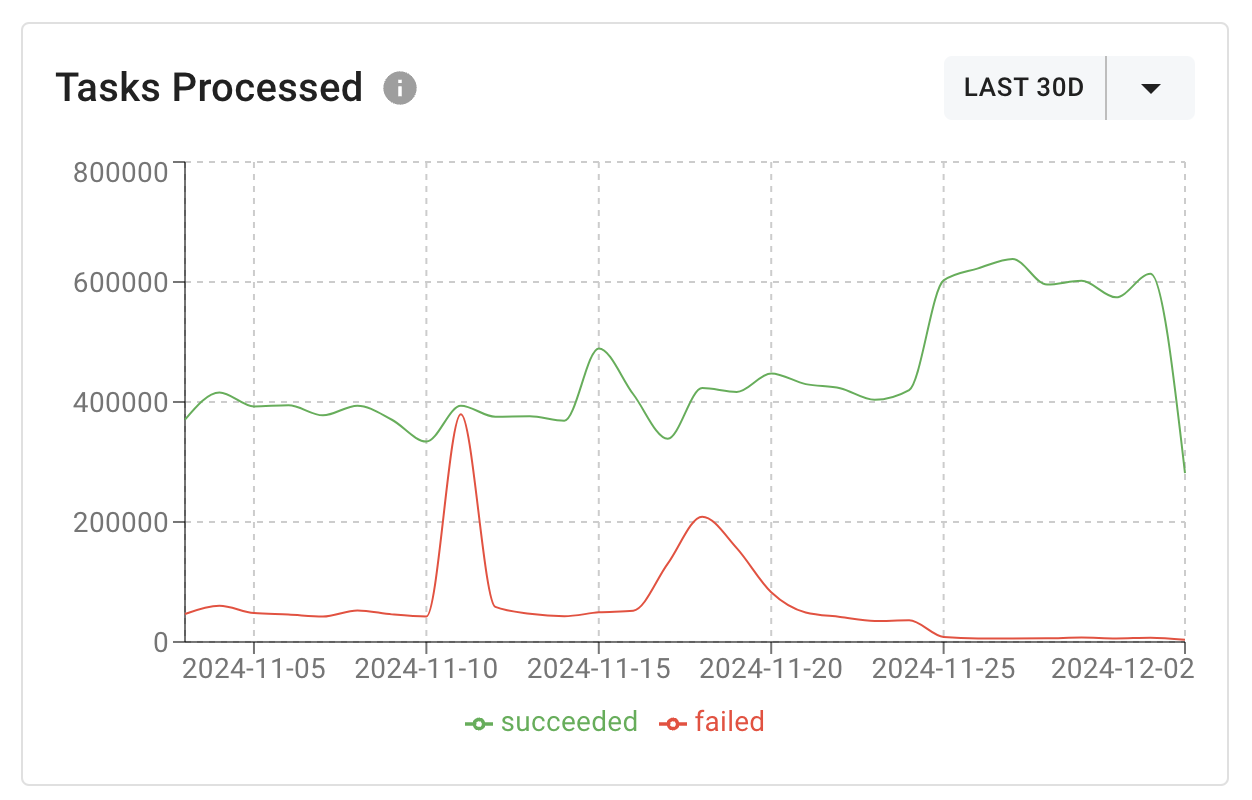

We began testing this in production and found some pretty interesting graph. One of our self-hosted customers was averaging about 100k failed delivery attempts/day (~10% of their traffic; they send about 600k events/day) due to zombie endpoints. Now it’s down to about 5k per day. That’s a 95% improvement. It turns out the ideal metric of success is the % of failed delivery attempts should be less than a number depending on the scale of deployment.

Event Performance Graph After One Week

Event Performance Graph After One Week

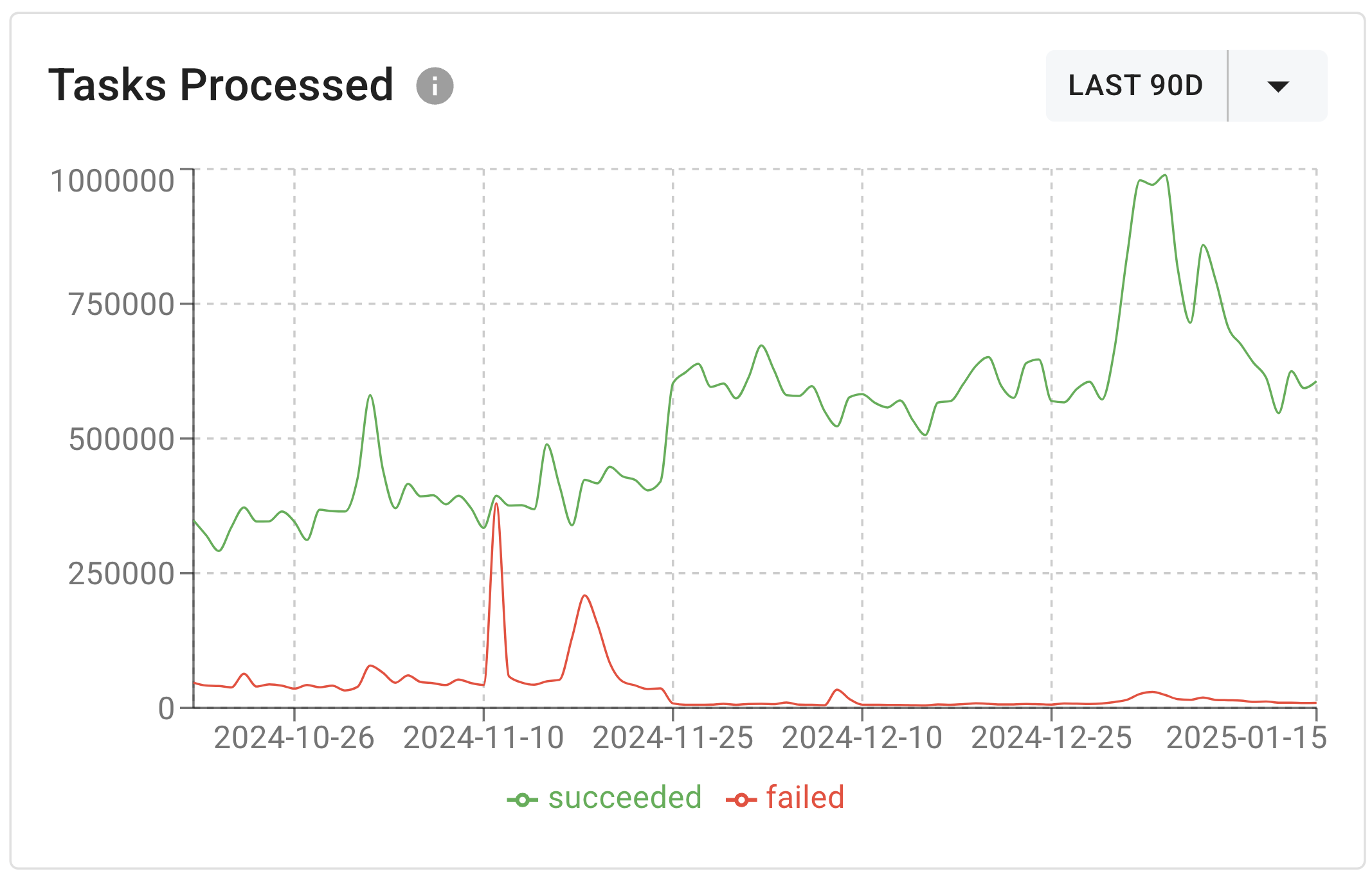

After a few months of integrating the circuit breaker the instance spends less time sending webhooks to bad endpoints, which is an overall improvement since more compute is spent sending webhooks to functioning endpoints.

Event Performance Graph After A Few Months

Event Performance Graph After A Few Months

Failure Scenarios

Applying Murphy’s law [5] to our design; some possible production failure scenarios include:

- The leader agent goes down during state evaluation: The state evaluation process is an atomic operation (we use a Redis pipeline for writes); it either all works or nothing works. At the next sample cycle, a new leader will be elected and will carry out state evaluation.

- All circuit keys are flushed from Redis. The following sample cycle will generate the

error_rateagain and rebuild the circuit’s state; eventually, zombie endpoints will be disabled again. - Redis is down: We have timeouts to ensure that clients are not hung up on Redis and the circuit “fails-open” as if it wasn’t there in the first place.

Other failure scenarios exist but these are the top of mind ones.

Appendix

- In the future, we plan to implement a proper leader-election algorithm, but for now, a distributed lock suffices.

- This summarizes the difference between a synchronous circuit breaker and an asynchronous breaker.

Feature Synchronous Circuit Breakers Asynchronous Circuit Breakers Execution Model Runs in the same thread/process as request Runs in separate threads/processes Operation Flow Blocks until health check/state evaluation completes Non-blocking health checks/state evaluation Store Local to the process Global (shared by all processes) Transition Mechanism Immediate Eventual Implementation Simple, relatively easy to follow order of execution More complex, harder to follow order of execution Complexity Lower architectural complexity Higher architectural complexity Error Handling Happens immediately in a caller Errors are non-blocking and are passed to callback handlers Use Cases Sequential operations, Based used in order-dependent flows, Simple request-response patterns Used in high-throughput systems, Promotes designing parallel operations in event-driven architectures Monitoring Real-time state visibility, state can be inspected using a debugger Eventually consistent state, state can be inspected using metrics System Load Can cause request queuing leading to backpressure Better load distribution due to non-blocking behaviour - Re: Trigger function in a multi-threaded environment behavior

- Rules or triggers to log bulk updates?

- Murphy’s Law

- Reliability, constant work, and a good cup of coffee